(Un)Becoming Her: The Woman Before She Was My Mother

This essay is a reflective narrative that unfolds through the act of flipping through an old photo album, encountering my mother not just as a parent, but as a girl, a young woman, a dreamer I never got to meet. As I pause at images of her sitting cross-legged with a chin resting lightly on her palm, wearing dresses she carried with unstudied confidence, or laughing under skies that knew nothing of what was to come, I find myself pulled into a paradox. I do not resemble her in my individuality, yet I carry her in my body.

The piece explores the fragmented intimacy of maternal inheritance — how it is not only blood or memory, but also posture, gaze, and emotional residue. I trace the silent gestures that repeat in me, from the way I carry my dupatta, to the way I slouch on the bed. Through these still moments captured on glossed paper, I feel a quiet kinship, a wish to walk alongside her in the blazing summers of her childhood, to witness her dream of picking lambs and running wild before the weight of motherhood settled in.

Yet this desire to know her more intimately is undercut by a sharp grief: every present-day conversation feels unfinished, suspended. We speak across a chasm of misalignments and missed timings. The essay meditates on this painful temporal disjuncture — the regret of not being able to grow together, and the deeper ache of realizing I am walking ahead, not intending to wait, even though a part of me longs to hold her hand just once more, as equals.

It is a piece that lives in the emotional textures of inheritance —

what we receive, what we resist, and what we’re left reaching for, long after the moment has passed.

Who tells a story?

My mother believes she has no story to tell. She laughs it off, sometimes giving me only a passing glance in the middle of her everyday routines, when I remind her that I am writing about her. She tells me to write about my father instead.

My mother believes she is not worth writing. That her story is not worth weaving into a journey to be published as a thought. A life is too ordinary, too unremarkable to be shaped into sentences, to be held in print. She urges me to write about my father—his brilliance, his achievements, his efforts, his compassion. And I keep failing to convey to her how much I already embody her story as my own. I see her story as a story of community, where people and places and words and songs, fabrics and jewellery, all spin around her like a long song, stretching across a diary’s pages, full of life, yet buried under the pretext of too mundane.

I see my mother’s story as a multitude of complexities, a layering of interwoven histories and kinships, a narrative embedded in flesh, blood, and memory. It is a story that holds the contradictions of love, grief, and detachment all at once…… A story that I share with her, and yet narrate it like someone else’s belonging….

The Woman Before She Was My Mother

Bhopal studio, early 1970s. My mother as a toddler, dressed in a traditional skirt and blouse, garland (haar) and flower bands (gajra) adorning her.

Agra, early 1970s. My mother posing with her late paternal uncle (Kaka) in front of the Taj Mahal.

My mother was born in the city of Bhopal, state of Madhya Pradesh, India, and spent her first five years there before moving to Mumbai for school. All her cousins stayed behind in Bhopal, so vacations and festivities meant going back to the familiar chaos of a joint family home. She talks about those early years with a kind of lightness — “chhan khel khelaychi, palaychi dhavaychi” — running around and playing endless games with cousins, never running out of company.

Even after the move, letters kept those ties alive. Long letters, pages filled with updates about birthdays, Rakshabandhan celebrations (Indian festival celebrating brother-sister bonds), and the small events that shape childhood — all of those still stored in our house, often taken out by me. Mumbai broughtits own circles of belonging: close friendships with her maitrini, and later, her first job. She remembers her daily train commutes vividly—one hour each way, morning and evening—becoming part of a group of regulars who would sing Shravan bhajans, Devi songs, Manglagaur tunes, and old Bollywood melodies together. There was laughter, shared food, and shared grief too.

A birthday greeting card sent to my mother by her cousin from Bhopal, 1980s.

She laughs now when she tells me how her relatives were always amazed at her ability to navigate the Mumbai locals so effortlessly during rush hour, especially with her slight, frail-looking physique at the time. But listening to her stories, I see how deeply she was shaped by the people around her. My mother grew up knowing love as constant and communal. She thrived among her people.

She didn’t have to learn love through absence or longing; it was already there—in her uncles and aunts, cousins and parents, their community of students (my grandparents held tuition classes in their home), and the neighbours in their chawl.

“We were not very rich,” she says to me often, “but we were very happy with everyone together.”

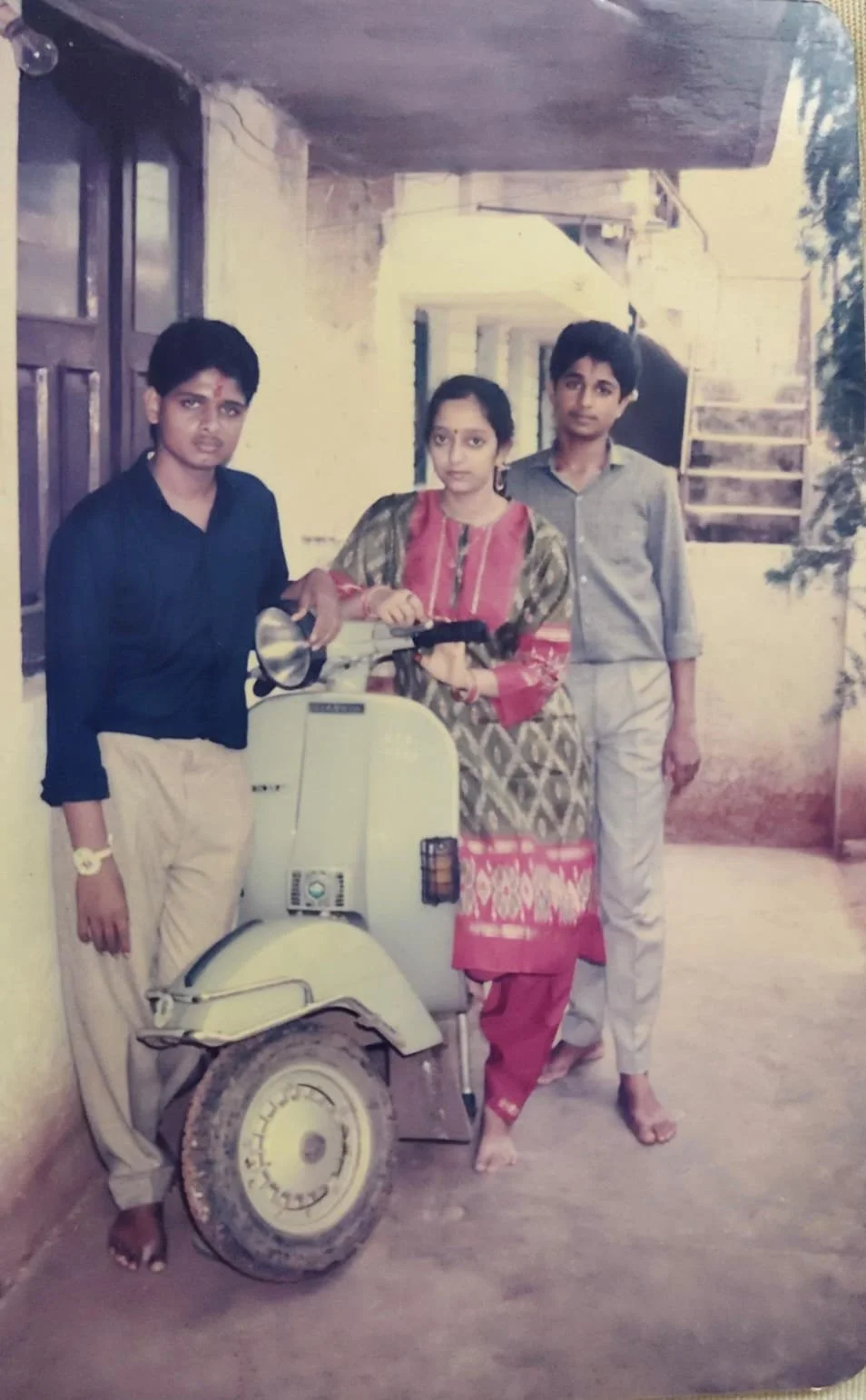

Bhopal, 1989. My mother posing with her brothers in their courtyard on Rakshabandhan.

Mulund home, Mumbai, early 1990s. My mother celebrating her birthday with all her neighbors.

There’s something profoundly south asian about this I feel. Something we very conveniently omit when we critique those same systems of family and community. Here in this context, communal care isn’t just a value, it’s a structure. Children grow up in the presence of many caregivers, learning early that relationships are not contained within the nuclear family. Love is shared, reciprocated, and woven into the everyday—through festivals celebrated in courtyards, borrowed ingredients from a neighbour’s kitchen, the comfort of sleeping in a cousin’s bed during vacations. This collective living doesn’t erase hardship, but it softens it. It makes happiness less fragile because it is sustained by many.

She once shared a memory from her childhood. My grandmother, her mother, was working as a school teacher then, and my mother’s older aunt stayed at home during the day, taking care of her and her cousins. There was an overwhelming bond among the women in the family—tender but strong, woven out of everyday care. Her aunt, who had no children of her own, loved my mother and all the cousins as if they were hers. And yet, she equally cherished my grandmother, her sister-in-law.

One day, my mother remembers asking her aunt the kind of question only a child would dare: Do you love me more, or my mother? Even now, as she tells me this story, there is a proud smile tugging at her lips—a subtle boastfulness of being raised by such women. Her aunt had simply smiled and said, “You are here because of your mother.”

My mother tells me how wise that answer was, how her aunt managed to hold multiple truths at once. She reminded a child that love is not a comparable measure, that nobody is a substitute for another. But she also quietly reaffirmed her solidarity with the other women in the house.

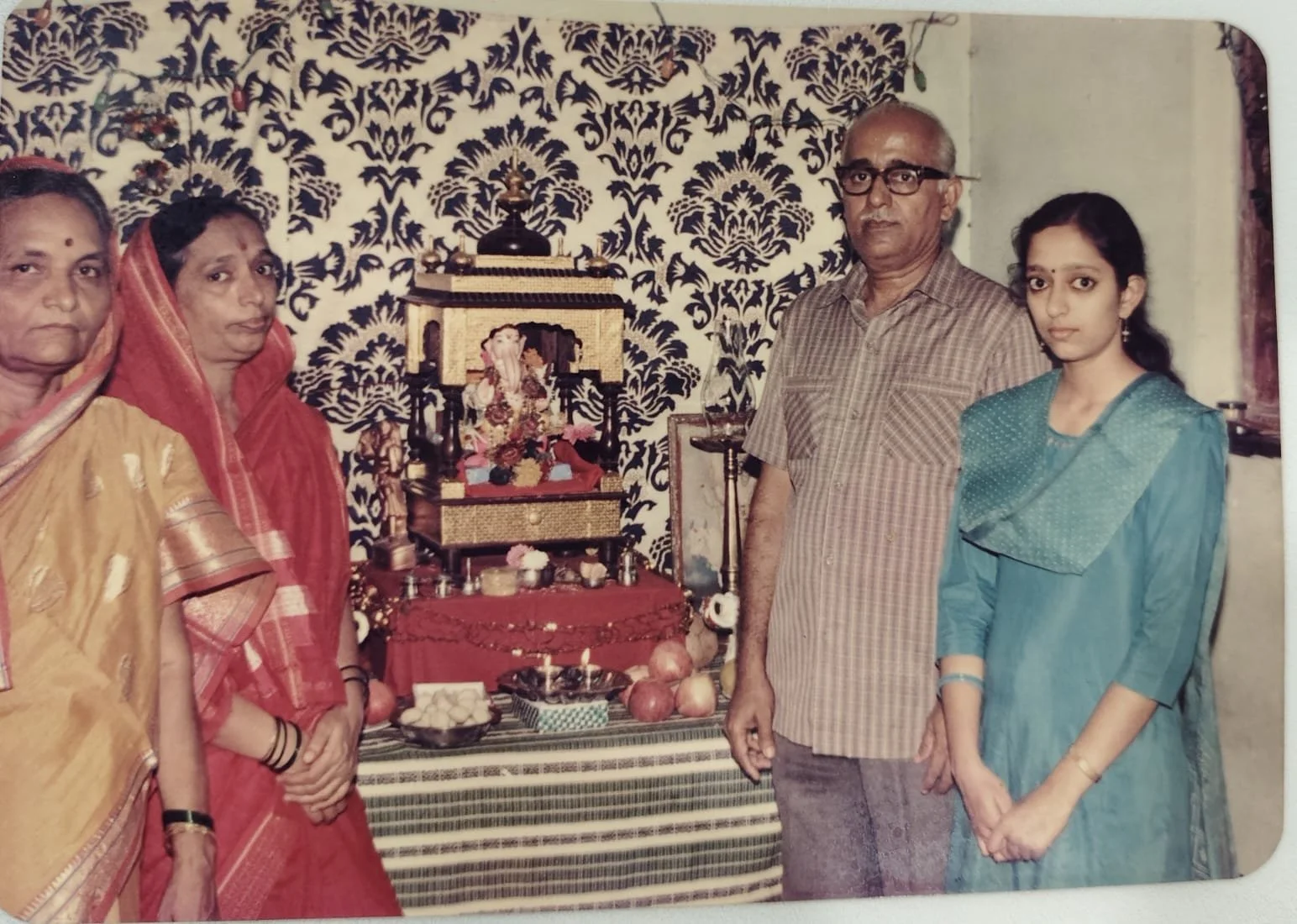

Mulund, Mumbai, 1985. Left to right: my mother’s late aunt, my grandmother, my late grandfather, and my mother posing in front of the family Ganesh idol during Ganesh Chaturthi celebrations at their home.

As my mother reflects on this memory, she notes how absent these nuances are from south asian, or especially Indian media today. So often, households are imagined as battlefields where women are pitted against each other—mothers-in-law against daughters-in-law, sisters against sisters-in-law. Rarely is there space for women to simply be with one another, let alone support and hold each other. Patriarchy thrives by creating an illusion of scarcity, convincing women that power and love are limited resources, that one must cut the other down to survive.

But my mother grew up aware of the audacity of that narrative. She saw something else. She believed in gendered solidarity because she had lived it. She learned to hold the women in her life closer, to believe that care could be shared without competition. It’s something she continues to replicate in her own marital family—with her in-laws, nieces, and nephews—an ethic of expansive love that resists the myth of scarcity.

I think about how different that feels from the individualistic ways we are often taught to think about family now. For my mother, community wasn’t something you had to seek out intentionally; it was the air she grew up breathing.

Looking at her, looking away

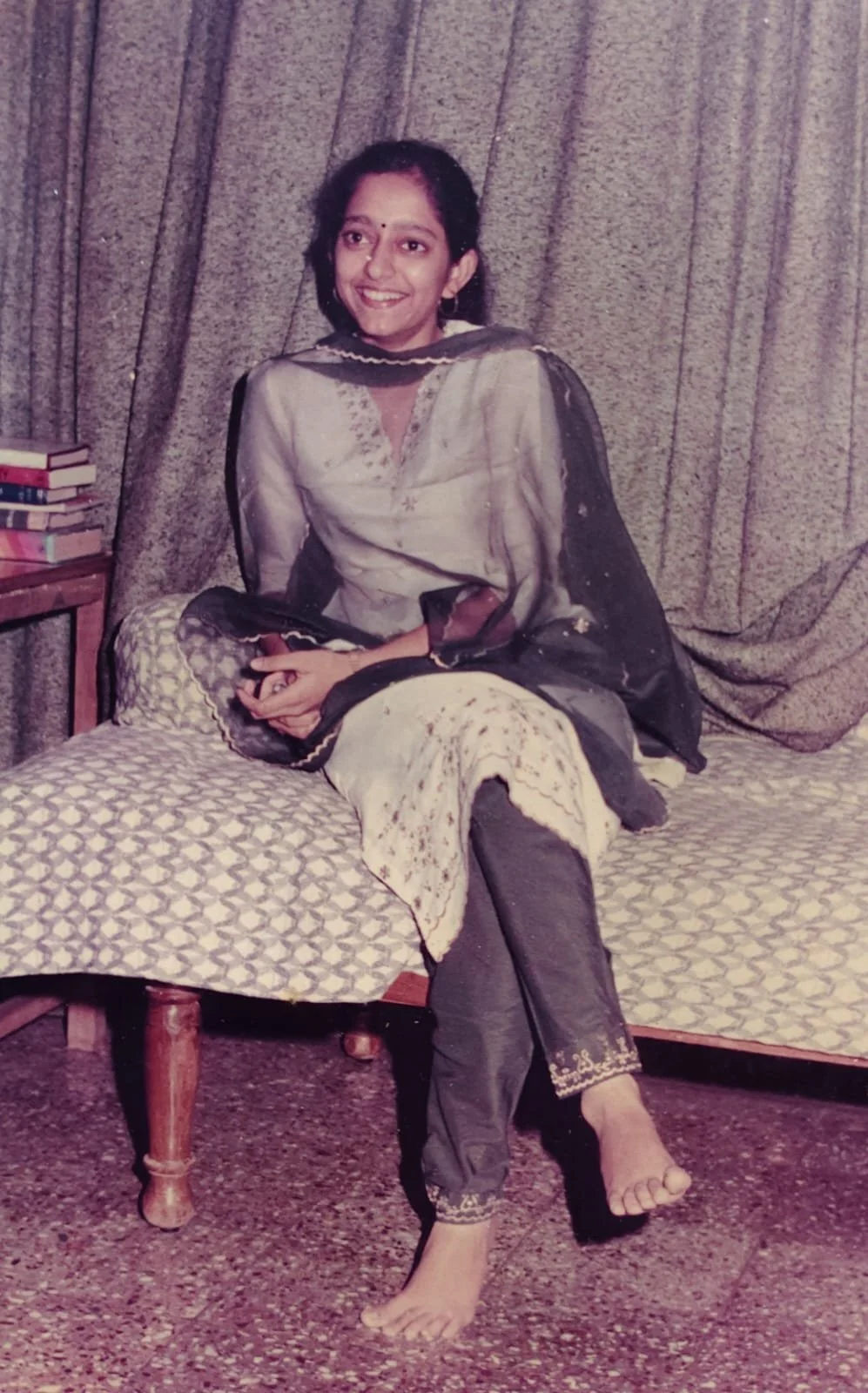

Her photographs stop me in my tracks. A loose-fitting kurta, a plain dupatta slipping easily off each shoulder, silver anklets circling both her feet. Her slightly curly, frizzy hair tied into a long plait cascading down her waist. My friends and family always comment on how similar we look, how alike our clothing choices are, even though I have never consciously tried to dress like her. But then I notice my own dupatta falling the same way, how I sit cross-legged in a salwar suit just like she does in those photographs. I see my bare feet where hers wore anklets and feel as if I am inside a portrait of my own—one that already exists.

Mumbai, late 1980s. My mother at her friend’s house in Mulund.

There’s a quiet tension in these resemblances. I have always wanted to hold on to my individuality, yet I can’t deny how much of her I carry in my body, even without trying. The photographs act like a temporal bridge, connecting us across time and across the distances—emotional and otherwise—that have shaped our relationship.

These are not just coincidences of posture or dress. They are small bodily repetitions that move silently through generations, perhaps tracing all the way back to my grandmother. They remind me how much of femininity is culturally coded, how daughters learn to inhabit a maternal aesthetic world almost without realizing it. And yet, there is also a politics to this—patriarchy often conditions women,especially in family structures, to disidentify from one another, to create distance in order to assert their own place.

I think of how much I have searched for belonging in their legacy, how much I want to see these inheritances as connection rather than erasure. To imagine that these gestures are not just repetitions of expectation but also living archives of the women before me. That even in the complexities of our relationship, my body remembers what theirs endured, how they moved, how they held themselves. And maybe, in some way, that memory allows me to hold them too.

Bhopal, early 1960s. My grandmother (age 26) posing in a saree with her colleagues from the teacher's community.

Her sarees were always perfectly draped and pinned— “Shubhangi sarkhi sadi tar konalach nesavta yet nahi” (“Nobody can drape a saree as good as your mother”), my mother’s best friend, someone I hold very close to as my own family, would say with pride. Every pleat sat in its exact place, her bangles and jewellery always matching, her dupatta neatly folded and tucked as though it had a life of its own.

There was a grace to her presentation, a sharp precision I could never quite replicate.

Dombivali, 1980s. My mother posing in a saree and traditional Maharashtrian jewellery, holding oil lamps during Diwali celebrations at her aunt’s house.

She has always loved music. Especially old Bollywood songs and the beautifully choreographed numbers of older cinemas. She loves Urdu ghazals, can sing every word by heart. She isn’t the best singer—in fact, she was rejected by the music teacher when she tried to take private lessons in her youth—but I don’t think she sings that badly.

She is known instead for her ability to know songs, to understand them fully. She recognizes a song within the first second of its opening notes. It’s a small ability, but one that makes me smile every time. My aunts and her friends often mention it—how well-versed she is, and even how she knows the meaning of every word. At this point, she can even decode the most difficult folk lyrics from regional songs. A vast vocabulary embodied through her love for music, a world of her own. She once shared with me how back during her cousin’s wedding she kept playing and singing the same songs of the then popular film Hum Aapke Hain Kaun (1994), and how everyone then begged her to stop repeating the same tunes!

My mother insists she is too practical to imagine, too realistic to be romantic. But I have always seen her differently. She carries a poetic heart, even if she hides it behind laughter. She hums words and tunes in the car or to herself at home, unaware of how much beauty she carries.

She claims she has no grace to dance, only a sense of rhythm sharp enough to catch when someone else falters—a trait, she says, that makes her my biggest critic since I began my own journey as a dancer. But I see her differently: full of gestures, her body speaking a language she doesn’t even notice.

Mulund, early 1990s. My mother posing at house in Mumbai.

After the initial awe of first encountering the photographs, I begin scanning the details secretly in my room, as though deciphering a code. She seemed almost trendy to me for her time, always attentive to the rhythms of everyday fashion. Her hair changed with the seasons of her life—long oiled plaits, then high ponytails, then the occasional bob cut. Printed kurtas formed a staple of her wardrobe, their patterns familiar even now, as though I had seen variations of them in my own closet. One hand always carried a single bangle, the other a watch—a balance I also follow, though my fondness for bangles has grown into a dozen colourful glass ones that clink at every movement. Her earrings were smaller,

daintier; mine are loud jhumkas. She preferred a Lucknowi kurta; I skip the bindi she wore with unthinking regularity. My grandmother, watching me study these images, remarks on the obvious: my eyes resemble hers, big and outlined in kajal, the same doe-shaped gaze preserved in the photograph. Perhaps that is what photographs do—they hold both tenderness and regret, reminding us not just of

what was, but also of what we wished had been.

Now, as I grow older and look back at photographs of my younger self standing beside her, a strange grief takes over me. There is an ache in those images, a reminder of the closeness I craved but never fully felt. I wonder what it would have been like to be able to sit next to the exact same version of her in those photos, exchange a few words looking straight into each other’s eyes. I wonder what it would be like, to speak to her when she wasn’t my mother.

Unbecoming: The duality of a daughter’s gaze

क्षणोक्षणी पडे, उठे, पर बळे, उडे बापडी,

चुके पथह, येउनी ितमत दृ िटला झापडी.

कती घळघळा गळे रु धर कोमलांगातुनी,

तशीच नजकोटरा परत पातली पक्षणी.

(She falls and rises every moment, yet gathers her strength and flies again,

Even when she strays from the path, dazed and blinded by fatigue.

How much blood gushes from her tender body,

And still, the little bird returns quietly to her nest.)

- ना.वा.टळक

I was recently reminded of a Marathi poem my grandmother used to recite to me in the afternoons to put me to sleep—Kevdhe He Kraurya (What Cruelty!) by Na. Va. Tilak. The poem is about a small mother bird, her wings torn and bleeding, yet struggling to reach her nest to feed and caress her babies one last time—to give them warmth, to give them love, to give them nurture. She collapses lifeless at the end.

I hated that poem as a child. I still do. But for my grandmother, it was a lesson she believed she had to pass on to me. While I waited each day for my mother to return from work, my grandmother must have felt a responsibility: to make sure I didn’t grow distant from my mother’s love, to remind me of her sacrifices even in her absence. The unflinching selflessness of that bird was not just a story; it was a cultural metaphor for motherhood.

Looking back, I realize it wasn’t only a reminder to me. It was a reminder to my grandmother herself—to hold on to the sacrificial ethic of mothering that shaped her life too. But even as a child, something in me resisted it. I didn’t want to believe that to be a mother meant to suffer quietly, to martyr yourself for love.

I think now about it, I never wanted my mother to be an image of relentless sacrifice, but rather, present, balanced, and self-sustaining. Not one who bleeds herself dry and calls it devotion, but one who can love deeply without erasing herself. My mother however believed in silent sacrifices and a kind of love marked by severity—tempered by emotional suppression. Her care often balanced on a fine line between discipline and emotional wounding—a line that continues to mark my memories. She wasn’t loud but could be tense; not strict, but disciplined. She ignored when she was upset, yelled when she was overwhelmed, blamed when she was hurt. All of this, unfamiliar to a younger me. I remember longing for a love that didn’t bleed while nurturing me, but instead nurtured itself alongside me.

I have known her love, but the grief remains. I remember very well her dressing me up, planning with me what to watch for dinner, taking days off when I was sick, showing up for my annual days in school, writing scripts for my school plays, recording my dances, going through my notebooks — all while navigating her own work. The memories that surface most strongly are not of warmth but of the

moments that felt like neglect, even if they weren’t intended as such. This is the quiet tension I still carry—the knowledge of her love and the feeling of its absence. It is a contradiction that refuses to resolve, a reminder of how care can wound when it demands too much of the giver.

Motherhood, in her world, was often framed as competition. There was the unspoken measuring of children’s achievements, their manners, their successes, as though one’s worth as a mother could be weighed through the lives of others. It must have been exhausting to live under that gaze, and perhaps that exhaustion sometimes bled into how she parented me.

There is also a grief that lives quietly between us—not death, but something like it. An anticipatory grief that has always complicated the present, making our moments together feel suspended, as though they might disappear at any second. I think this grief makes it harder for us to reach one another fully, as though we are both already mourning what we might lose.

Looking back, I can see how these layers—her fears, her labour, her grief—shaped the relationship we share today. They don’t negate her love. But they do explain why it sometimes felt harder to find each other in the everyday, why so much of our connection lives in quiet gestures rather than open words.

My mother is known to be strong-willed and efficient. Doctor’s appointments, talking to nurses in hospitals, chatting easily with guests, tending to the sick—she has always done it all. And stopped when it was too much. I see my family and relatives rely on her strength, and yet I find myself distancing from it.

That distance began in childhood, born from fear. She was a professional working woman with a 9-to-5 job and a stable income, coming home in the evenings only to talk about discipline—homework, school projects, exams. I never learned to rely on her. Her presence felt too big, too authoritative for the younger me….. And now, when I no longer fear retribution and can finally see her as a person, I wonder if it’s too late to begin relying on her. Especially now, when I see time slipping through my hands, when I watch her aging, when I feel the quiet dread of knowing I will lose her one day. There is grief in this. Not only the grief of never fully seeing her as who she was before she became my mother, but also the grief of not wanting to get too close anymore.

Knowing, Loving, Seeing

She asks me why there are fewer pictures of her on the wall compared to my friends. She demands priority—weekends, trips, outings, events, dinners, tea times, meal times—she wants my complete company and no less. It feels almost like an overcompensation for all the time lost to those years of working before retirement. Maybe she too feels time slipping away.

She imagines a future where I marry in a few years, where tradition will separate us, where I will no longer be just her daughter. A future where she won’t be able to demand the same authority over me

again.

Thane, 1995. The kanyadaan ritual at my parents’ wedding, performed by my grandparents along with my mother’s paternal uncles and aunts.

For her, marriage was never an entrapment; it was the opposite, a union that secured happiness. Even now, she often repeats how lucky she was, how her parents chose the right man for her, how life unfolded as it should have. It is a memory she idealizes, perhaps because it reaffirms her trust in her parents and their choices. In some way, she projects that same idealization onto me: the belief that if she finds me the ‘right’ partner, everything else will align on its own. She frames it as responsibility—an obligation she owes me, a final parental act that will resolve my life, as though happiness can be handed

down like a family heirloom.

I give off a bitter laugh whenever she makes these remarks. I know life has not come as easily to me as it did to her, that I will not be spared in the same ways. Her faith feels intrusive. A refusal to see how different our lives and circumstances are, how her version of happiness may not be mine. Yet, beneath that idealization is something far more vulnerable—the fear of losing proximity, of losing relevance

once tradition redraws the boundaries of our relationship. For her, marriage signifies not only my future but her impending absence from its centre.

I see my mother as a dreamer. Her smile seems to demand happiness, full of self-worth—never meek in asking, never afraid of hoping. I remember her once telling my father that she wanted to hold a baby lamb in the middle of a grazing field, her voice soft but certain. I have seen her seek calm in the imagination of open spaces, vast seas, and dark monsoons. She loves the idea of journeying—though her knee pains now keep her closer to home, I know her heart still wanders.

And yet now, she claims over and over again that everything about her revolves around me—an obsession, if I must say. One that leaves me feeling lonelier than she realises. She speaks often of how she doesn’t desire anything else, only my happiness. But even then, I feel left behind and walking ahead at the same time. No matter how much of a dreamer I see in her, I know we cannot dream at the same time anymore. Her dreams seem to have quieted, gone. Mine remain unconstructed, unchased.

I keep desiring her in a way she no longer exists, in the way I see her in old photographs or imagine her in stories. I see her tired now, resting, walking away from life gradually, while I keep walking toward it, relentless, struggling to keep up with the demands of sociality. And in all the tensions and complexities, the thing I seek and grieve the most is her company—back then….. even now.

Mumbai, mid-1980s. My mother looking through her childhood photo album.

Mumbai, mid-1980s. My mother looking through her childhood photo album.

Written by Vedanti Hindurao